《纽约时报》最近发布了一篇关于当前大学录取乱象的文章,通过详细的案例和深入的分析,揭示了录取过程中的不公平和不透明。这篇文章揭示了在2024年的申请季中,学生和家庭面临的各种挑战,从录取政策的变化到助学金系统的崩溃,再到“可选考试”政策的复杂性。

2023-24年的录取季不仅仅是这种年度仪式中疯狂姿态和高压猜测的逐步增加,使之看起来像是学术版的“饥饿游戏”。这一年有所不同。一些广泛讨论的因素和一些鲜为人知的因素结合在一起,将这个过程推向了一个新领域,在这个领域中旧规则不再适用,甚至连把关者也似乎不知道新的规则是什么。

通过艾维和拉尼亚的2个申请故事案例能看到录取过程的严酷现实。艾维虽然拥有顶尖的学术背景和经济支持,但在多所顶尖大学的申请中仍然遭遇拒绝。而拉尼亚尽管克服了生活中的种种困难,却因助学金申请的延迟和系统故障而不得不重新考虑自己的选择。

在这些故事背后,我们看到了一个更加广泛的问题:当前的大学录取系统越来越“飘忽不定”。作者呼吁大学和政策制定者采取更透明和公平的录取标准,确保所有学生都能在公平的竞争环境中获得应有的机会。

在大学录取的战场上,每一年的录取季都仿佛是一场豪赌,而2024年更是变成了一个极端的赌局。在教育行业里每天都能感受到申请过程中那种无形的压力、焦虑和不确定性。这些年来,我们见证了太多学生和家庭在这个过程中经历的酸甜苦辣。

文章中的艾维,这个拥有顶尖学术背景的女孩,本应在顶尖大学中游刃有余,但现实却是她在多所梦校面前碰壁。她的经历反映了如今录取过程的严苛和残酷,即使是那些学术成绩拔尖、家境殷实的学生,也无法确保能够进入心仪的大学。这让我们不得不反思:到底是什么让这些曾经相对确定的事情变得如此不可预测?

另一方面,拉尼亚的故事则充满了励志与遗憾。她在面对生活困境的同时,依然坚持追求卓越。但即使是这样一个坚韧不拔的学生,也因助学金系统的混乱而受到阻碍。FAFSA系统的崩溃和延迟,让她无法及时获得经济支持,迫使她重新考虑自己的选择。

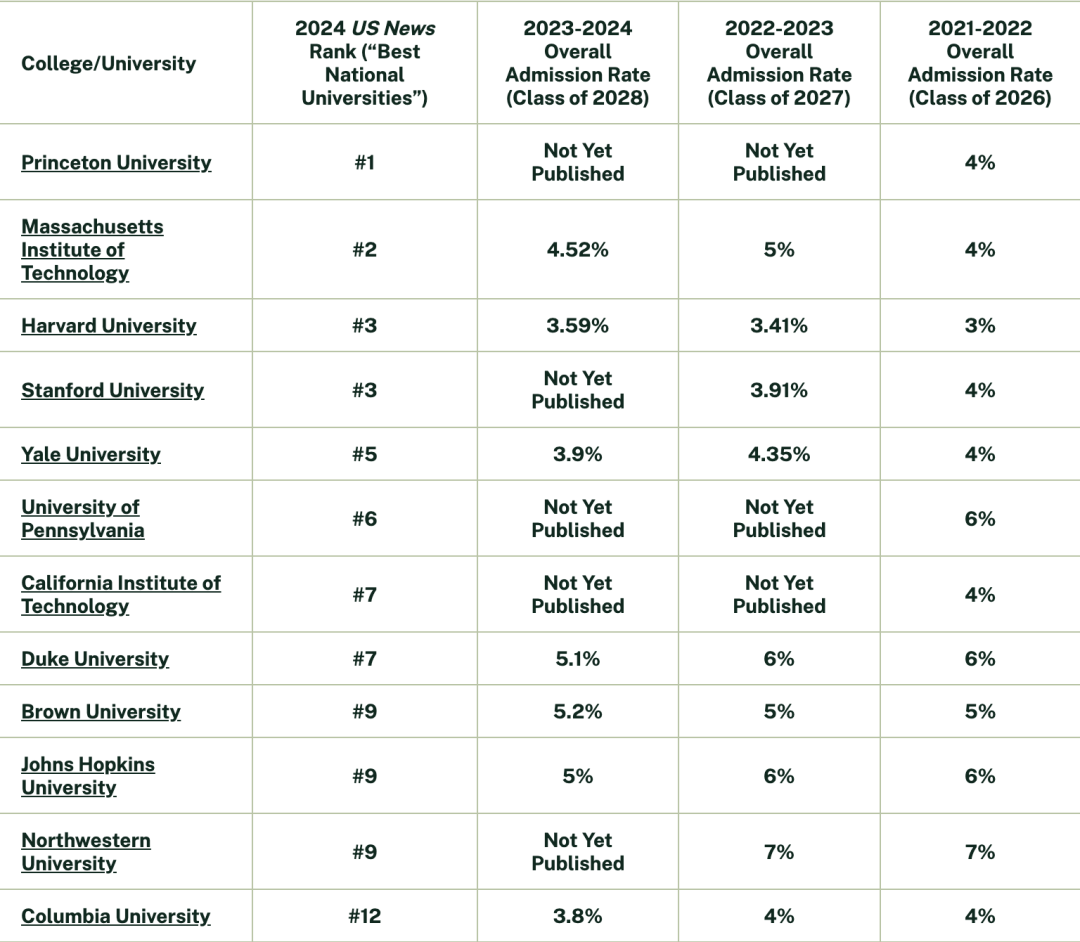

近年来,大学录取政策发生了诸多变革。Test-optional政策虽然初衷是好的,但在实际操作中却带来了新的问题。申请者往往只提交高于中位数的成绩,导致中位数不断上升,反而让那些没有提交成绩的学生处于劣势。与此同时,随着越来越多的大学采用“可选考试”政策,学生和家庭在决定是否提交考试成绩时也面临更多的困惑。

此外,提前决定(Early Decision)策略虽然能够提高学校的录取率,但也让很多学生在没有足够信息的情况下做出仓促的决定。这种策略在无形中加剧了教育资源的不公平分配,让那些无法承担全额学费的学生处于不利地位。

今年的FAFSA表格改版虽然旨在简化申请流程,但实际效果却适得其反。系统故障和发布延迟让许多家庭无法及时获得助学金信息,进而影响了他们的大学选择。对于低收入和第一代大学生来说,这无疑是一个巨大的打击。

面对这些挑战,大学和政策制定者必须采取行动,改善现状。文章作者也说明了以下是一些可能的改进措施:

1. 透明的录取标准:

大学应公开明确的录取标准,让申请过程更加透明和公平。

2. 公平的助学金政策:

大学在提供录取通知时,应该同时提供明确的助学金信息,避免学生在不了解实际费用的情况下做出决定。

3. 多样化的招生策略:

大学应该加强与低收入和第一代大学生的联系,通过各种途径扩大招生的多样性。

4. 合理使用AI技术:

在使用AI技术时,大学应确保其应用的公平性和透明性,避免对申请者造成不公平的影响。

最根本的解决办法还在于系统的改革,推动整个教育系统的公平和进步。在此期间,我们能做的只有努力抓住可见的“确定性”。在面对录取过程中的种种不确定性时,我们可以专注于那些可以控制的因素:提升学术成绩、参与有意义的课外活动、撰写出色的个人陈述、争取强有力的推荐信等。

通过这些具体的努力,我们可以增加自身的竞争力,即使在充满变数的环境中,也能为自己争取更多的机会。同时,保持积极的心态和灵活的应变能力也是关键。无论结果如何,重要的是我们在这一过程中学到的技能和获得的成长。

纽约时报原文:

Selective college admissions have been a vortex of anxiety and stress for what seems like forever, inducing panic in more top high school seniors each year. But the 2023-24 admissions season was not just an incremental increase in the frantic posturing and high-pressure guesswork that make this annual ritual seem like academic Hunger Games. This year was different. A number of factors — some widely discussed, some little noticed — combined to push the process into a new realm in which the old rules didn’t apply and even the gatekeepers seemed not to know what the new rules were.

It happened, as these things often do, first gradually and then all at once.

It started with a precipitous rise in the number of people clamoring to get in. The so-called Ivy-Plus schools — the eight members of the Ivy League plus M.I.T., Duke, Chicago and Stanford — collectively received about 175,000 applications in 2002. In 2022, the most recent year for which totals are available, they got more than 590,000, with only a few thousand more available spots.

The quality of the applicants has risen also. In 2002, the nation produced134 perfect ACT scores; in2023 there were 2,542. Over the same period, the United States — and beyond it, the world — welcomed a great many more families into the ranks of the wealthy, who areby far the mostlikely to attend an elite college. Something had to give.

The first cracks appeared around the rules that had long governed the process and kept it civilized, obligating colleges to operate on the same calendar and to give students time to consider all offers before committing. A legal challenge swept the rules away, freeing the most powerful schools to do pretty much whatever they wanted.

One clear result was a drastic escalation in the formerly niche admissions practice known as early decision.

Then Covid swept through, forcing colleges to let students apply without standardized test scores — which, as the university consultant Ben Kennedy says, “tripled the number of kids who said to themselves, ‘Hey, I’ve got a shot at admission there.’” More applications, more market power for the schools and, for the students, an ever smaller chance of getting in.

Last year, the Supreme Court’s historic decision ending race-based affirmative action left colleges scrambling for new ways to preserve diversity and students groping in the dark to figure out what schools wanted.

Finally, this year the whole financial aid system exploded into spectacular disarray. Now, a month after most schools sent out the final round of acceptances, many students still don’t have the information they need to determine if they can afford college. Some will delay attending, and some will forgo it entirely, an outcome that will have lasting implications for them and, down the line, for the economy as a whole.

These disparate changes had one crucial thing in common: Almost all of them strengthened the hand of highly selective colleges, allowing them to push applicants into more constricted choices with less information and less leverage. The result is that elite admissions offices, which have always tried to reduce the uncertainty in each new year’s decisions, are now using their market power to all but eliminate it. This means taking no chances in pursuit of a high yield, the status-bestowing percentage of admitted students who enroll. But low uncertainty for elite colleges means the opposite for applicants — especially if they can’t pay the full tuition rate.

Canh Oxelson, the executive director of college counseling at the Horace Mann School in New York, says: “This is as much uncertainty as we’ve ever seen. Affirmative action, the FAFSA debacle, test-optionality — it has shown itself in this one particular year. Colleges want certainty, and they are getting more. Families want certainty and they are getting less.”

In 2024, the only applicants who could be certain of an advantage were those whose parents had taken the wise precaution of being rich.

The Early Bird Gets the Dorm

For Ivy Wydler, an elite college seemed like an obvious destination, and many of her classmates at Georgetown Visitation Preparatory School in Washington, D.C., were headed along the same trajectory. After her sophomore year of high school, she took the ACT and got a perfect score — on her first try, a true rarity. Her grades were stellar. So she set her sights high, favoring “medium to big schools, and not too cold.”

Touring campuses, she was dazzled by how great and exciting it all seemed. Then she visited Duke, and something clicked. She applied in the binding early decision round.

It’s a consequential choice. Students can do so at only one college, and they have to promise to attend if accepted, before knowing what the school’s financial aid offer will be. That means there is at least a chance an applicant will be on the hook for the full cost, which at Duke is $86,886 for the 2024-25 year. Students couldn’t be legally compelled to attend if they couldn’t afford it, but by the time they got the news, they would have already had to withdraw their other applications.

If full tuition isn’t a deal killer, as it wouldn’t be for Ivy’s family, the rewards are considerable. This year,just over 54,000high school seniors vied to be one of only 1,750 members of Duke’s incoming class. The 6,000 who applied in the early decision round were three times as likely to get in as the 48,000 who applied later.

Until recently, early decision was a narrow pathway — an outlier governed, like the rest of this annual academic mating season, by a set of mandatory practices laid out by the National Association for College Admission Counseling, which is made up of college admissions officers and high school counselors. Those rules said, for example, that colleges couldn’t recruit a student who was already committed to another school or actively encourage someone to transfer. Crucially, the rules said that colleges needed to give students until May 1 to decide among offers (noting early decision, which begins and ends in the fall, as a “recognized exception”).

The Justice Department thought those rules ran afoul of the Sherman Antitrust Act, which bars powerful industries from colluding to restrain competition. At the end of 2019, NACACagreedto a settlement mandating that the organization “promptly abolish” several of the rules and downgrade the rest to voluntary guidelines. Now, if they chose to, colleges had license to lure students with special offers or benefits, to aggressively poach students at other schools and to tear up the traditional admissions calendar.

At that point, nothing restrained colleges from going all in on early decision, a strategy that allows them to lock in students early without making any particular commitments about financial aid. Of the 735 first-year students thatMiddlebury Collegeenrolled last year, for example,516were admitted via binding early decision. Some schools have a second round of early decision, and even what amounts to an unofficial third round — along with an array of other application pathways, each with its own terms and conditions.

With the rules now abandoned, colleges got a whole new bag of tricks. For example, a school might call — at any time in the process — with a one-time offer of admission if you can commit on the spot to attend and let go of all other prospects. Hesitate and it’s gone, along with your chances in subsequent rounds. “We hear about colleges that are putting pressure on high school seniors to send in a deposit sooner to get better courses or housing options,” says Sara Harberson, the founder of Application Nation, a college advising service.

To inform these maneuvers, colleges lean on consultants who analyze applicant demographics, qualifications, financial status and more, using econometric models. High school seniors think this is checkers, but the schools know it’s chess. This has all become terrifying for students, who are first-time players in a game their opponents invented.

Application season can be particularly intimidating for students who, unlike Ivy, did not grow up on the elite college conveyor belt. When Rania Khan, a senior in Gorton High School in Yonkers, N.Y., was in middle school, she and her mother spent two years in a shelter near Times Square. Since then she and her younger brother have been in the foster system.

Despite these challenges, she has been a superb student. In ninth grade, Rania got an internship at Google and joined a research team at Regeneron, a biotechnology company. She won a national award for herstudyof how sewage treatment chemicals affect river ecosystems. Looking at colleges, she saw that her scores and credentials matched with those of students at the very top schools in the country.

One of the schools she was most drawn to was Barnard. “I like that it’s both a small college and” — because it’s part of Columbia — “a big university. There are a lot of resources, and it’s a positive environment for women,” she said. And it would keep her close to her little brother.

Barnard now fills around 60 percent of its incoming class in the early decision round, giving those students a massive admissions advantage. It would have been an obvious option for Rania, but she can’t take any chances financially. She applied via the general decision pool, when instead of having a one in three chance, her odds were one in 20.

Officially, anyone can apply for early decision. In practice it’s priority boarding for first-class passengers.

Unstandardized Testing

When selective colleges suspended the requirement for standardized testing, it didn’t really seem like a choice; because of the pandemic, a great many students simply couldn’t take the tests. The implications, however, went far beyond mere plague-year logistics.

The SAT was rolled out in 1926 as an objective measure of students’ ability, absent the cultural biases that had so strongly informed college admissions before then. It’s been the subject of debate almost ever since. In 1980, Ralph Naderpublished a studyalleging that the standardized testing regimen actually reinforcedracial and gender biasand favored people who could afford expensive test prep. Many educators have come back around toregarding the testsas a good predictor of academic success, but the matter is far from settled.

Remarkably, students still take the exams in the same numbers as before the pandemic, but far fewer disclose what they got. Cindy Zarzuela, an adviser with the nonprofit Yonkers Partners in Education who works with Rania and about 90 other students, said all her students took the SAT this year. None of them sent their scores to colleges.

These days, Cornell, for example, admits roughly 40 percent of its incoming class without a test score. At schools like theUniversity of Wisconsinor theUniversity of Connecticut, the percentage is even higher. In California, schools rarely accept scores at all, being in many cases not only test-optional, but also “test-blind.”

The high-water mark of test-optionality, however, was also its undoing.

Applicants tended to submit their scores only if they were above the school’s reported median, a pattern that causes that median to be recalibrated higher and higher each year. WhenCornellwent test-optional, its 25th percentile score on the math SAT jumped from 720 to 750. Then it went to 760. The ceiling is 800, so standardized tests had begun to morph from a system of gradients into a yes/no question: Did you get a perfect score? If not, don’t mention it.

The irony, however, was that in the search for a diverse student body, many elite colleges view strong-but-not-stellar test scores as proof that a student from an underprivileged background could do well despite lacking the advantages of the kids from big suburban high schools and fancy prep schools. Without those scores, it might beharder to make the case.

Multiply that across the board, and the result was that test-optional policies made admission to an elite school less likely for some diverse or disadvantaged applicants. Georgetown and M.I.T. were first to reinstate test score requirements, and so far this year Harvard, Yale, Brown, Caltech, Dartmouth and Cornell have announced that they will follow. There may be more to come.

The Power of No

On Dec. 14, Ivy got an answer from Duke: She was rejected.

She was in extremely good company. It’s been a while since top students could assume they’d get into top schools, but today they get rejected more often than not. It even happens at places like Northeastern, a school nowranked 53rd in the nation by U.S. News& World Report — and not long ago, more than100 slots lowerthan that. It spends less per student on instruction than theBoston public schools.

“There’s no target school anymore and no safety school,” saysStef Mauler, a private admissions coach in Texas. “You have to have a strategy for every school you apply to.”

Northeastern was one of the 18 other schools Ivy applied to, carefully sifting through various deadlines and conditions, mapping out her strategy. With Duke out of the picture, her thoughts kept returning to one of them in particular: Dartmouth, her father’s alma mater. “My mom said, ‘Ivy, you love New Hampshire. Look at Dartmouth.’ She was right.” She had wanted to go someplace warm, but the idea of cold weather seemed to be bothering her less and less.

Meanwhile Rania watched as early decision day came and went, and thousands of high school seniors across the country got the best news of their lives. For Rania, it was just another Friday.

A Free Market in Financial Aid

In 2003, a consortium of about 20 elite colleges agreed to follow a shared formula for financial aid, to ensure that they were competing for students on the merits, not on mere dollars and cents. It sounds civilized, but pricing agreements are generally illegal for commercial ventures. (Imagine if car companies agreed not to underbid each other.) The colleges believed they were exempt from that prohibition, however, because they practiced “need-blind” admissions, meaning they don’t discriminate based on a student’s ability to pay.

In 2022, nine current and former students from an array of prestigious collegesfiled a class-action antitrust lawsuit— laterbacked bythe Justice Department — arguing that the consortium’s gentlemanly agreement was depriving applicants of the benefits of a free market. And to defang the defense, they produced a brilliant argument: No, these wealthy colleges didn’t discriminate against students who were poor, but they sure did discriminate in favor of students who were rich. They favored thechildren of alumniand devoted whole development offices to luring the kinds of ultrarich families that affix their names to shiny new buildings. It worked: Early this year, Brown, Columbia, Duke, Emory and Yale joined the University of Chicago inconceding, and paying out a nine-figure settlement. (They deny any wrongdoing.) Several other schools are playing on, but the consortium and its rules have evaporated.

This set schools free to undercut one another on price in order to get their preferred students. It also gave the schools a further incentive to push for early decision, when students don’t have the ability to compare offers.

For almost anyone seeking financial aid, from the most sought-after first-round pick to the kid who just slid under the wire, the first step remained the same: They had to fill out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid form, or FAFSA.

As anyone knows who’s been through it — or looked into the glassy eyes of someone else who has — applying for financial aid can be torture at the best of times. This year was the worst of times, because FAFSA was broken. The form, used by the government to determine who qualifies for federal grants or student loans, and by many colleges to determine their in-house financial aid, had gotten a much-needed overhaul. But the new versiondidn’t work, causing endless frustration for many families, and convincing many others not even to bother. At mid-April, finished FAFSA applications were down29 percentcompared with last year.

“The FAFSA catastrophe is bigger than people realize,” saysCasey Sacks, a former U.S. Department of Education official and now the president of BridgeValley Community and Technical College in West Virginia, where 70 percent of students receive federal funds.

Abigail Garcia, Rania’s classmate and the 2024 valedictorian of their school, applied to in-state public colleges as well as Ivies. She couldn’t complete the FAFSA, however, because it rejected her parents’ information, the most common glitch. She has financial aid offers from elite schools, all of which use a private alternative to the government form, but she can’t weigh them against the public institutions, because they are so severely delayed.

For most students, 2024’s FAFSA crisis looks set to take the uncertainty that began last fall and drag it into the summer or beyond. “That’s going to reduce the work force in two to four years.” Ms. Sacks says. “FAFSA completions are a pretty good leading indicator of how many people will be able to start doing the kinds of jobs that are in highest demand — registered nurses, manufacturing engineers, those kinds of jobs.”

As the FAFSA problem rolls on, it could be that for the system as a whole, the worst is still to come.

Can Any of This Be Fixed?

On the numbers, elite college applicants’ problems are a footnote to the story of college access. The Ivy-Plus schools enroll less than 1 percent of America’s roughly15 million undergraduates. If you expand the pool to include all colleges that are selective enough to accept less than a quarter of applicants, we’re still talking about only6 percentof undergraduates. The easiest way to alleviate the traffic jam at the top is to shift our cultural focus toward the hundreds of schools that offer an excellent education but are not luxury brands.

Luxury brand schools, however, have real power. In 2023, 15 of 32 Rhodes scholars came from the Ivies, nine from Harvard alone. Twenty of this year’s 38 Supreme Court clerks came from Harvard or Yale. If elite colleges’ selection process is broken, what should we do to fix it?

Here’s what we can’t do: Let them go off and agree on their own solution. Antitrust law exists to prevent dominant players from setting their own rules to the detriment of consumers and competitors.

Here’s what we won’t do: Legislate national rules that govern admissions. Our systems are decentralized and it would take a miracle for Congress not to make things worse.

But here’s what we can do: Hold the schools accountable for their processes and their decisions.

Institutions that receive federal funds — which include all elite colleges — should be required to clearly state their admissions criteria. Admissions as currently practiced are designed to let schools whose budgets run on billions of taxpayers dollars do whatever they want. Consider Stanford’s guidance to applicants: “In a holistic review, we seek to understand how you, as a whole person, would grow, contribute and thrive at Stanford, and how Stanford would, in turn, be changed by you.” This perfectly encapsulates the current system, because it is meaningless.

Colleges should also not be allowed to make anyone decide whether to attend without knowing what it will actually cost, and they should not be allowed to offer better odds to those who forgo that information. They should not offer admissions pathways tilted to favor the rich, any more than they should offer pathways favoring people who are white.

It just shouldn’t be this hard. Really.

The Envelope Please …

Ivy has the highest academic qualifications available inside the conventional system, and her family can pay full tuition. Once upon a time, she would have had her pick of top colleges. Not this year.

Over the course of the whole crazy admissions season, the school she had come to care about most was Dartmouth.

Along with the other seven Ivies, Dartmouth released this year’s admissions decisions online on March 28, at 7 p.m. Eastern. Ivy was traveling that day, and as the moment approached, she said, “I was on the bed in my hotel room, just repeating, ‘People love me for who I am, not what I do. People love me for who I am, not what I do.’”

She was rejected by Duke, Vanderbilt, Stanford, Columbia and the University of Southern California, where Operation Varsity Blues shenanigans could once guarantee acceptance but, as Ivy discovered, a perfect score on the ACT will not. She landed on the wait list at Northeastern. She was accepted by Michigan and Johns Hopkins. And Ivy was accepted at both her parents’ alma maters: the University of Virginia and Dartmouth, where she will start in September.

For Rania, the star student with an extraordinary story of personal resilience, the news was not so good. At Barnard, she was remanded to the wait list. Last year only 4 percent of students in that position were eventually let in. N.Y.U. and the City University of New York’s medical college put her on the wait list, too.

A spot on a wait list tells applicants that they were good enough to get in. By the time Rania applied to these schools, there just wasn’t any room. “It was definitely a shock,” she said. “What was I missing? They just ran out of space — there are so many people trying to get into these places. It took two weeks to adjust to it.”

She did get lots of other good news, a sheaf of acceptances from schools like Fordham and the University at Albany. But then came the hardest question of all: How to pay for them? Some offered her a financial aid package that would leave her on the hook for more money than undergraduates are allowed to take out in federal student loans. Even now, some colleges haven’t been able to provide her with financial aid information at all.

Rania had all but settled on Hunter College, part of the City University system. It’s an excellent school, but a world away from the elite colleges she was thinking about when she started her search. Then at almost the last moment, Wesleyan came through with a full ride and even threw in some extra for expenses. Rania accepted, gratefully.

For Rania, the whole painful roller coaster of a year was over. For so many other high school seniors, the year of broken college admissions continues.

最后,希望每一个追求梦想的学生都能够在公平的竞争中实现他们的目标,而不再被卷入这场残酷的“学术版饥饿游戏”。