Economics is, of course, a difficult thing to define in its entirety. Perhaps this is to do with how it has changed over the course of its existence. Part of the problem lies in Jacob Viner’s frustrating, amusing sentiment of “economics is what economists do”: frankly, an unhelpful and unilluminating thought. It would surely help to have something we can all agree on; to say, in unison, where the boundary lies, for to find a unifying expression of what economics is supposed to do should be an excellent way of reining in the boundless trivialities in which economists indulge. Economics is not a beautiful field, certainly, but it is an especially practical one in our material age. If the orthodoxy doesn’t know what problems it is trying to solve and why it is trying to solve them, all it is doing is intellectual fiddling.

From the observation of undergraduate study at Cambridge, it is notable the extent to which closed-form, mathematical ideas predominate. I don’t think this is exclusive to this university, either. Important economic papers tend to include models, usually mathematical. Closed-form expressions of complex reality – ones which take inputs and produce an output – may be useful for the purposes of analysis and testing in a purely scientific environment, but an economy is far from scientifically observable entity. Is it wise to wrap such a complex reality as an economic environment into a model with a few inputs and a few outputs? It seems dubious that it can ever work with the same intellectual rigour that the natural sciences enjoy, and that economics covets.

Doubtless, models need not account for every possibility, but when laws such as those implied in models are as incomplete as they frequently are, you can only expect economic hypotheses to hold while their assumptions, explicit or implicit, also hold true. Famously, the stable Phillips curve, which at the time seemed remarkably predictive, utterly broke down 15 years after its proposition during the stagflation of the 1970s. A science whose propositions can last only 15 years is no science at all.

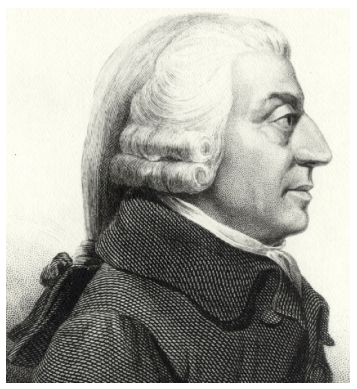

It hasn’t always been like this, either; the text which more than anything else founded the field of economics, Adam Smith’s magnum opus The Wealth of Nations, still carries remarkable strength today because it paints in broad strokes about the nature of value, of individual and social behaviour and the virtues of capital accumulation. Keynes’ General Theory, too, has remained relevant (and adaptable) by virtue of its delivery via prose, instead of mathematics. Hicks’ bastardised mathematical implementation of Keynesian ideas leaves out a great deal of nuance from Keynes’ work, and suffers in its relevance as a result.

In general, it can be said that the fixation on mechanical economics is a direct descendant of the Keynesian short- run revolution. Analysis of short-run fluctuations and policy (at least in the realm of macroeconomics) are so à la mode, and have been for so long, that Classical long- run thinking, of improvement and progress and the welfare of the citizenry, have been neglected, much to the detriment of political thought. Economists should be the ones investigating the changes which need to be made in order to create better and more prosperous societies across the world; a pedantic and inward obsession with the short run is, in the long run, futile.

The heroes of economics are those who drive society forward, who find answers to questions that need answering. And it is our society’s namesake, Alfred Marshall, and those who took after him – Hicks, Friedman and Samuelson, for instance – who had inherited a dismal science and made it even more dismal. The philosophical, thoughtful, elegant, insightful, progressive works of Adam Smith, John Maynard Keynes, Karl Marx and David Ricardo, to name but a few: they represent the study of economics at its best. It is their qualities, over the faux- scientism of modern orthodox economics, which the field should emulate.

From top to bottom: economists Milton Friedman, John Maynard Keynes, and John Hicks. On the right, the father of modern economics, Adam Smith.