题目:Is a strong state a prerequisite or an obstacle to economic growth?

题目翻译:强大的国家是经济增长的先决条件还是障碍?

论文译文:

1989 年,资本主义美国在冷战中战胜共产主义苏联导致弗朗西斯·福山宣布“历史的终结”,以及“西方自由主义(自由贸易和“有限国家”)的可行系统替代方案完全耗尽。 ' [1]接下来的几十年并没有证明这一点。尽管历史学家的领域是过去,但这并不妨碍他们关注现在。现在,对“西方理念”的强烈反对者,中国已经崛起为美国全球实力的挑战者,避免了 2008 年经济衰退的最严重时期,并在 2014 年以购买力平价调整后的 GDP 超过美国。[2]同时,西方民主的力量似乎处于低谷:例如,在英国,69% 的人对民主的运作方式天生不满意。[3]因此,“北京共识”的兴起

——一个国家的政治垄断以换取经济增长——可能比以往更让历史学家感兴趣。“共识强大”国家的各个方面——税收、监管、国家对暴力的垄断——当然是 GDP 健康增长所必需的。[4]然而,我想调查负责任的“霸道国家”在多大程度上推动了经济增长。三个“方面”将这些与共识强大的状态区分开来:

-

政治合法性并非建立在纳税人的选票之上。

-

经济为政治服务,反之亦然。

-

社会自由明显受限。

历史学家可以通过追溯 1978 年至 91 年间俄罗斯和中国从共产主义向资本主义的平行过渡,分离出“霸权国家”对经济增长的影响;他们在 1990-2000 年间不同的政治经济结果;以及他们最近收敛到霸道国家。尽管没有规定模板“先决条件”,但我认为,由于这些年来取得的一些显著成功,管理良好的霸道国家已经有力地挑战了华盛顿共识。

直到 1980 年代,苏联和中国的国家都是强大的国家,可以在很大程度上满足这三个方面的要求。在苏联,共产党(苏共)发挥了领导作用。国家机构 Gosplan 负责监督命令经济(很大程度上与全球市场隔绝),言论自由最终受到克格勃的限制。然而,苏联的经济增长随着时间的推移而恶化:在 1970-80 年间,GDP 平均每年增长 1.7%,与许多西方经济体相比较低。[5]此外,正如米勒所说,国家很强大,但也很弱,以至于 Gosplan 游说团体开始发挥经济运行的直接权力,而不是苏共总书记。[6]商业显然不为政治服务。戈尔巴乔夫受到改革苏联国家的启发,采取措施将苏联重新融入全球市场。改革始于 1987-88 年,涉及减少政府对企业的控制。由于在如此短的时间内没有建立令人满意的社会主义市场框架,据估计,到 1990 年,影子经济增长到名义 GDP 的 11%(即 1500 亿美元),其中一些人在黑市上的官方收入翻了一番. [7]然后在1990年2月,戈尔巴乔夫确实通过取消规定苏共“领导作用”的宪法条款,致命地削弱了国家控制。这一决定有效地消除了苏联的第一和第三方面;实际上,II 已经不在了。这种政治/经济解体的正反馈循环一直持续到 1991 年 12 月苏联解体。苏联这个强大的国家未能实现维持自身所需的经济增长。然而,正是政治控制的放弃导致它在政治和经济上分崩离析,形成了一个相辅相成的循环。

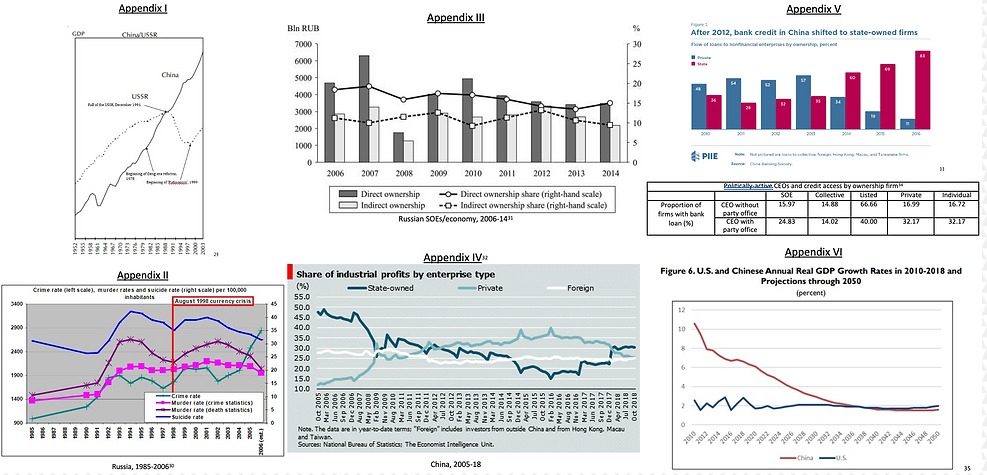

相反,在毛泽东时代的中国,增长也同样平庸。1953-78 年间,实际 GDP 年增长率为 4.7%,但稳定性被早期五年计划的高点、大跃进(1958-62 年)和随后的文化大革命(1966-76)。[8]1952-88 年间,中国的 GDP 明显落后于苏联(见附录 I)。然而,中国的不同之处在于,共产党(CPC)并没有诉诸政治自由化来纠正这一点。1976 年文化大革命的结束、毛泽东的逝世和 1978 年四人帮的倒台,加强了中国共产党的经济改革者,尤其是邓小平。他们开展了一系列改革,主要是提高大型国有企业(SOEs)管理者的财务自主权。至关重要的是,这些都是以比苏联“休克疗法”更渐进的方式完成的。到 1988 年,中国的 GDP 已超过苏联。然而,虽然中共允许更大的自治权,但它与苏共的不同之处在于保持对商业机构的监督,以及对中国政治制度的绝对控制。[9]中共通过镇压 1989 年春天(戈尔巴乔夫访问北京时)天安门广场的民主示威以及此后的所有类似运动来巩固控制。在苏共牺牲政治和经济控制的同时,中共保留了政治霸权(I,III),尽管放松了管制,但仍对经济事务进行了实质性控制(II)。

不同的战略在 1978-1999 年间产生了不同的经济结果。苏共后的俄罗斯政治陷入了改革所引发的经济无政府状态。1989 年,整个联邦的犯罪率增加了 32%,这清楚地表明了国家控制的衰落。[10]政治控制的瓦解导致了 1991 年 8 月的政变失败,这也使戈尔巴乔夫——总统——被软禁。在 1991 年 12 月的新奥加雷沃会谈中解散苏联,戈尔巴乔夫没有被邀请。新俄罗斯联邦的相对软弱导致了地理上的解体:一些国家宣布自治(例如车臣和鞑靼斯坦),1998 年,加里宁格勒当局宣布不再向莫斯科缴纳税款。[11]莫斯科无法在亏损公司中执行联邦范围内的税收、反腐败措施或效率标准。这些尤其具有提供就业的杠杆作用,这是为叶利钦赢得选票的关键,到 1996 年已累积拖欠 13.7 万亿卢布。[12]前国有企业的这种权力反过来又限制了莫斯科减少其在经济中的份额,从而在能源价格下跌时增加了对衰退的责任(如 1997-98 年)。为了减少现在阻碍俄罗斯经济的苏联巨额消费者补贴,叶利钦被迫在 1993 年炮击俄罗斯议会大楼。因此,政治控制的解体以及相关的后果导致 GDP 在 1990 年代下降了 35%。[13]

相比之下,中国没有出现类似的问题。地理整合得以保留。对民主运动的镇压巩固了中国共产党的政治统治。这使得领导层能够进行经济密集型改革,以提高中国国有企业的效率(现在,不像俄罗斯那样不可触碰)。例如,朱镕基在 1997 年至 2003 年期间裁减了多达 4000 万亏损国企职工,裁员人数减少了 37%。[14]通常,这些后来被私有化。这些广泛的权力,加上放松管制以提高效率,使得俄罗斯不可能实现惊人的经济增长,这主要是由于对其领导层的限制(以及物质和人口限制)。虽然 1993 年俄罗斯和中国的经济规模几乎相同,但到 2003 年,中国的经济规模是中国的三倍。[15]中共培育的强大国家,似乎能够进行具体的改革,而忽略不满者,而在俄罗斯较弱的国家,任何追求这一点的领导人都可能被选下台。

也许弗拉基米尔普京认识到这些弱点。米勒的“普京经济学的三大支柱”是:

-

强化中央权威。

-

防止民众不满。

-

提高业务效率,只为服务I和II。[16]

这似乎是在效仿中共的政策并拒绝了苏共的政策。在叶利钦努力与富有的敌对权力集团打交道时,普京首先利用他与安全部门的联系来约束敌对集团,然后拉拢他们以实现他的政治和经济目标。这方面的一个例子是前俄罗斯首富米哈伊尔·霍多尔科夫斯基的出纳。作为能源巨头尤科斯 (Yukos) 的所有者,他曾试图在 1997-98 年危机之后避免惩罚性税收措施。普京的回应是在 2003 年下令逮捕他并监禁他八年。对俄罗斯超级富豪征税,使预算在 2000 年代初重新平衡,政府储蓄最终使他们免受 2007-8 年金融危机的影响。[17]俄罗斯国家目前约占国内生产总值的 35%,尽管能源和银行业出现了大幅增长,这也是北京的关键战略领域。[18]在俄罗斯,国家对经济的“间接”参与扩大了国家的存在,这是一种更为微妙的方法,似乎是苏联过度监管和叶利钦式监管不足之间的第三种方式。然而,它并没有自动产生增长:人口和外交限制限制了 GDP 增长,因此在 2013-18 年间,可支配收入每年下降。[19]因此,普京的新战略是否会促进更强大的俄罗斯国家的经济增长还有待观察。

中国共产党认为对企业的控制对其生存至关重要。尽管在 1978 年至 2017 年间,国有企业的就业人数/人口下降了 80%,产出份额下降了三分之二,但习近平一直致力于提高国有企业的效率和财富。顺便说一句,自 2015 年以来,私营部门的利润份额稳步下降,而 2018 年——自 2011 年以来首次——国有企业的毛利润超过了私营企业。[20]国有企业占中国制造业 500 强的 50%。与此同时,14/16 在中国境外经营的最大的中国公司是国有企业。[21]让他们服从中国共产党的政治特权——让中国富裕,增加外国直接投资存量,从而增强中国的全球实力——通常是一种互惠互利的安排。中共还将政治控制扩大到私营部门,为中国企业制造垄断或影响力:例如银行卡公司银联,直到 2014 年,中共一直垄断中国银行卡行业,反对美国竞争对手。68% 的中国私营企业有党组织2016年,外资企业占比70%;与此同时,欧莱雅、迪斯尼、陶氏化学等企业都设有党委,并在中国办公室摆出锤子和镰刀。[22]此外,党的隶属程度也影响了民营企业积累银行贷款的能力(见附录五)。1980 年代至 2000 年代放松管制无疑产生了惊人的经济增长,1979 年至 2018 年期间 GDP 平均增长 9.5%。[23]然而,在预测到 2020 年之后的增长率将下降(见附录六)的情况下,中国共产党似乎正在加强其对经济的参与以保持其权力,并将这些资产引导到海外以在全球范围内建立权力:关键的例子是充满风险的“一带一路”倡议(BRI),潜在的 8 万亿美元投资。[24]因此,很难否认中国共产党是商业的“沉默伙伴”,是一个经济和政治强大的国家,但其形式比上个世纪的共产主义国家要微妙得多。腐败和低效率并不少见,并在一定程度上阻碍了经济增长。然而,俄罗斯注意到了中国的成功:就在最近,统一俄罗斯的代表开始访问中国,了解中国如何在不牺牲政治控制的情况下开放经济。[25]

归根结底,我不会将强大的国家规定为经济增长的“先决条件”,因为正如几十年来在苏联和毛泽东时代的中国所看到的那样,政治实力阻碍了增长。此外,美国的自由放任政策和英国的新自由主义政策有助于这些国家的经济增长。然而,强大的国家不一定是障碍。保持政治控制,同时培养对企业的政治所有权更加细致和分散的方法,迄今已使中国共产党受益。当今世界的霸道国家越来越多地挑战西方自由主义思想将预示“历史终结”的观点。自然,腐败和党派利益集团破坏了增长,正如苏联晚期在经济上与中国分道扬镳时所看到的那样,尽管进行了改革。[26]然而,在习近平的领导下,中共对腐败采取了强硬态度。[27]无论如何,如果中国的“一带一路”[28]成功地建立了中共寻求的全球影响力,华盛顿可能会发现其政治和经济处方将开始在全球范围内受到价值观截然不同的权力集团的成功挑战。

Footnotes

1 F. Fukuyama, ‘The End of History?’, The National Interest, no. 16 (1989), pp. 3-18: 1.

2 W.M. Morrison, ‘China’s Economic Rise’, Congressional Research Service (2019), p. 10.

3 R. Wike & S. Schumacher, ‘Satisfaction with democracy’, Pew Research Centre, 27 February 2020. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/02/27/satisfaction-with-democracy/.

4 See D. Acemoglu, ‘Politics and Economics in Strong and Weak States’, NBER Working Paper 11275 (2005), pp. 19-25. Acemoglu gives as examples the United Kingdom (with its NHS and welfare system), and Sweden.

5 P. Hanson, The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Economy: Economic History of the USSR 1945-1991, Routledge (Abingdon, 2003), p. 131.

6 C. Miller, The Struggle to Save the Soviet Economy: Mikhail Gorbachev and the Collapse of the USSR, North Carolina U.P. (Chapel Hill, NC, 2016), p. 57: ‘In theory, the CPSU controlled the economy, but in reality the industries controlled the party.’

7 R. Parker, ‘Inside the Collapsing Soviet Economy’, The Atlantic, June 1990.

8 A. Maddison, Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run, 960-2030, OECD Development Centre (2007), p. 150.

9 Quoted in R. McGregor, ‘How the state runs business in China’, The Guardian, 25 July 2019.

10 A. Ogushi, ‘The disintegration of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union’, PhD thesis (University of Glasgow, 2005), p. 231. See also Appendix II.

11 M. Gilman, No Precedent, No Plan: Inside Russia’s 1998 Default, M.I.T. Press (Cambridge, MA, 2010), pp. 192-3.

12 Miller, Putinomics: Power and Money in Resurgent Russia, North Carolina U.P. (Chapel Hill, NC, 2018), p. 15.

13 A. Aslund, Building Capitalism: The Transformation of the Former Soviet Bloc, Cambridge U.P. (Cambridge, 2002), pp. 118, 308. Russian male life expectancy dropped nearly 10%, and suicides rose 60%, showing the extent of economic stress.

14 Economist Intelligence Unit, ‘Are state-owned enterprises reformable?’, 18 December 2018.

15 World Bank, Sodruzhestya nezavisimykh gosudartsv v 2005g (Moscow, 2006).

16 Miller, Putinomics, p. xiii.

17 It can also go the other way: the political subjection of the Venezuelan state oil company, PDVSA, means that its workers are hired on a basis of political allegiance to the United Socialist Party of Venezuela. In 2002, when PDVSA employees went on strike to protest the policies of Chávez, 19,000 were fired, and Intevep, the research and development arm of PDVSA lost 80%, reducing its ability to innovate and compete globally. 1976-92, 29% of PDVSA revenues went towards costs, and 71% to the government. Because of this, Chávez and his successor Nicolás Maduro have been accused of treating it like a ‘piggybank’.

18 See G. Di Bella, O. Dynnikova, S. Slavov, ‘The Russian State’s Size and its Footprint: Have They Increased?’, IMF WP 19/53 (2019). See also Appendix III.

19 Miller, ‘Russians Lower Their Standards’, Foreign Policy, 11 February 2019.

20 EIU, 2018. See also Appendix IV.

21 ‘Chinese Multinationals Gain Further Momentum’, Vale Columbia Centre and Fudan University survey, 9 December 2010. Available at: https://emgp.org/wpcontent/uploads/2018/07/China_2010.pdf.

22 McGregor, ‘How the state runs business’.

23 Morrison, ‘China’s Economic Rise’, summary.

24 A. Bruce-Lockhart, ‘China’s $900 billion New Silk Road. What you need to know’, World Economic Forum, 26 June 2017. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/06/china-new-silk-road-explainer/. It is estimated that 80% of funds invested in Pakistan, 50% in Myanmar, and 33% in Central Asia will be lost (J. Kynge, ‘How the Silk Road plans will be financed’, Financial Times, 9 May 2016). However, the trade off for this is an increase in Chinese hard power: land collaterals for debt in Kyrgyzstan (where per capita debt was $703 in 2018) or the entire Hambanthota Port in Sri Lanka (See M. Abi-Habib, ‘How China Got Sri Lanka to Cough Up a Port’, New York Times, 25 June 2018. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/25/world/asia/china-sri-lanka-port.html). In addition, it may prove to be a boon for the Chinese workforce, since 89% of BRI contracts will go to Chinese corporations.

25 J. Kurlantzick, State Capitalism: How the Return of Statism is Transforming the World, O.U.P. USA (New York, NY, 2016), p. 111.

26 Miller, The Struggle to Save the Soviet Economy, p, 178: ‘Where the Soviet Union diverged from China, it was because powerful interest groups obstructed Gorbachëv’s policies’. Elsewhere, a school of thought argues that the new “interest group” in Russian politics is not economic, but military-political: the old guard of the KGB, the new FSB and SVR security services. For the best piece on this, see C. Belton, Putin’s People: How the KGB Took Back Russia and then Took on the West, William Collins (London, 2020).

27 In 2016, Xi Jinping released a statement saying that ‘one million’ Chinese officials had been punished for corruption between 2013- 16 (https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-37748241).

28 For an interesting and suggestive investigation of the Belt and Road Initiative, refer to P. Frankopan, ‘The Roads to Beijing’, in The New Silk Roads: The Present and Future of the World, Bloomsbury (London, 2019), pp. 87-151.

Graphs

29 Maddison, Chinese Economic Performance, p. 61.

30 V. Popov, ‘China’s rise, Russia’s fall: Medium term perspective’, TIGER Working Paper Series No. 99 (2007), p. 10.

31 A. Abramov, A. Radygin & M. Chernova, ‘State-owned enterprises in the Russian market: Ownership structure and their role in the

economy’, Russian Journal of Economics, vol. 3, no. 1 (2017), pp. 1-23, fig. 6.

32 EIU, 2018.

33 N.R. Lardy, ‘State Sector Support in China Is Accelerating’, PIIE, 28 October 2019.

34 V. Nee & S. Opper, ‘On politicized capitalism’ (2006), p. 41, table 7.

35 Morrison, ‘China’s Economic Rise’, p. 9; EIU database.

Bibliography

I. Monographs

Brown, A., The Gorbachev Factor, Oxford U.P. (Oxford, 1996)

--- The Rise and Fall of Communism, Vintage (London, 2010)

Gao, M., The Battle for China’s Past: Mao and the Cultural Revolution, Pluto Press (London, 2018)

Garnaut, R., Song, L., & Woo, W.T., China’s New Place in a World in Crisis: Economic, Geopolitical and Environmental Dimensions, ANU Press (Canberra, 2009)

Gilman, M., No Precedent, No Plan: Inside Russia’s 1998 Default, MIT Press (Cambridge, MA, 2010)

Gustafson, T., Crisis amid Plenty: The Politics of Soviet Energy under Brezhnev and Gorbachev, Princeton U.P. (Princeton, NJ, 1989)

Hanson, P., The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Economy: An Economic History of the USSR 1945-1991, Routledge (Abingdon, 2003)

Hobsbawm, E., The Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century 1914-1991, Abacus (London, 1995)

Kotkin, S., Armageddon Averted: The Soviet Collapse, 1970-2000, Oxford U.P. (New York, NY, 2008) Kurlantzick, J., State Capitalism: How the Return of Statism is Transforming the World, Oxford U.P. (New York, NY, 2016)

Maddison, A., Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run, 960-2030, OECD Development Centre (2007). Available at: http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/Maddison07.pdf.

McGregor, R., The Party: The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers, Penguin (London, 2013) Miller, C., The Struggle to Save the Soviet Economy: Mikhail Gorbachev and the Collapse of the USSR, North Carolina U.P. (Chapel Hill, NC, 2016)

--- Putinomics: Power and Money in Resurgent Russia, North Carolina U.P. (Chapel Hill, NC, 2018) Shleifer, A. & Treisman, D., Without a map: political tactics and economic reform in Russia, M.I.T. Press (Cambridge, MA, 2000)

Sinenlnikov-Muryvlvev, S., Buidzhetnyi Krizis v Rossii, 1985-1995. Evrazia (Moscow, 1995) Stent, A., Putin’s World: Russia Against the West and With the Rest, Twelve (New York, NY, 2019) Westad, O.A., The Cold War: A World History, Penguin (London, 2017)

ii. Articles, papers and theses

Abramov, A., Radygin, A., & Chernova, M., ‘State-owned enterprises in the Russian market: Ownership structure and their role in the economy’, Russian Journal of Economics, vol. 3, no. 1 (2017), pp. 1-23, fig. 6. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405473917300016.

Acemoglu, D., ‘Politics and Economics in Strong and Weak States’, NBER Working Paper 11275 (2005). Available at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w11275.pdf

Allen, R.C., ‘The Rise and Decline of the Soviet Economy’, Revue canadienne d’économique, vol. 34, no. 4 (2001), 859-81. Available at: https://content.csbs.utah.edu/~mli/Economics%207004/Allen- 103.pdf.

Di Bella, G., Dynnikova, O., Slavov, S., ‘The Russian State’s Size and its Footprint: Have They Increased?’, IMF WP 19/53 (2019). Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2019/03/09/The-Russian-States-Size-and-its- Footprint-Have-They-Increased-46662.

Economist Intelligence Unit, ‘Are state-owned enterprises reformable?’, 18 December 2018. Available at: http://country.eiu.com/article.aspx?articleid=1697451553&Country=China&topic=Economy.

Ferdinand, P., ‘Russia and China: Converging Responses to Globalization’, International Affairs, vol. 8, no. 4 (2007), 655-80. Available at: www.jstor.org/stable/4541804.

Fukuyama, F., ‘The End of History?’, The National Interest, vol. 16 (1989), 3-18. Available at: www.jstor.org/stable/24027184.

Gat, A., ‘The Return of the Authoritarian Great Powers’, Foreign Affairs, July/August 2007 issue. Available at: http://online.sfsu.edu/jgmoss/PDF/635_pdf/No_59_Authoritarian_Great_Powers.pdf.

Giavazzi, F. & Tabellini, G., ‘Economic and Political Liberalizations’, NBER Working Paper 10657 (2004). Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=579804.

Kagan, R., ‘The End of the End of History’, The New Republic, 23 April 2008. Available at: https://newrepublic.com/article/60801/the-end-the-end-history.

Kohli, A., ‘States and Economic Development’, Brazilian Journal of Political Economy, vol. 29, no. 2 (2009), 212-27. Available at: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/rep/v29n2/03.pdf.

Lardy, N.R., ‘State Sector Support in China Is Accelerating’, Peterson Institute for International Economics, 28 October 2019. Available at: https://www.piie.com/blogs/china-economic-watch/state- sector-support-china-accelerating.

Morrison, W.M., ‘China’s Economic Rise: History, Trends, Challenges, and Implications for the United States’, Congressional Research Service, June 2019. Available at: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL33534.pdf.

Nee, V. & Opper, S., ‘On politicized capitalism’ (2006). Available at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4421/7f35372c8d8070f348e24fa6e4c47a08f334.pdf

North, D.C., ‘Institutions’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 5, no. 1 (1991), 97-112. Available at: https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jep.5.1.97.

North, D.C., Wallis, J., Weingast, B., ‘Violence and the Rise of Open-Access Orders’, Journal of Democracy, vol. 20, no. 1 (2009), 55-68.

Ogushi, A., ‘The disintegration of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union’, PhD thesis (University of Glasgow, 2005). Available at: http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4406/1/2005OgushiPhD.pdf.

Popov, V., ‘China’s rise, Russia’s fall: Medium term perspective’, TIGER Working Paper Series No.99 (2007). Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1037081

Przeworski, A. & Limongi, F., ‘Political Regimes and Economic Growth’, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 7, no. 3 (1993), 51-69. Available at: www.jstor.org/stable/2138442.

Roll, R., & Talbott, J., , ‘Political and Economic Freedoms and Prosperity’ (2003). Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228851565_Political_and_economic_freedoms_and_prosperity.

Stadler, A., ‘Strong States Make for a Strong Civil Society’, Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory, vol. 79 (May 1992), 29-32.

Tabellini, G., ‘The Role of the State in Economic Development’, CESIFO Working Paper 1256 (2004). Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=565921.

Wacziarg, R. & Welch, K.H., ‘Trade Liberalization and Growth: New Evidence’, NBER Working Paper 10152 (2003). Available at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w10152.pdf.

iii. E-media

Huang, Y., ‘China Has a Big Economic Problem, and It Isn’t the Trade War’, The New York Times, 17 January 2020. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/17/opinion/china-economy.html

Lin, Z., ‘Chinese Communist Party needs to curtail its presence in private businesses’, South China Morning Post, 25 November 2018. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/economy/china- economy/article/2174811/chinese-communist-party-needs-curtail-its-presence-private.

McGregor, R., ‘How the state runs business in China’, The Guardian, 25 July 2019. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jul/25/china-business-xi-jinping-communist-party-state- private-enterprise-huawei

Miller, C., ‘Is Putin Repeating the Mistakes of Brezhnev’, The Wall Street Journal, 9 March 2018. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/is-putin-repeating-the-mistakes-of-brezhnev-1520609347.

--- ‘Russians Lower Their Standards: Life may be getting harder in Russia, but Putin doesn’t care’, Foreign Policy, 11 February 2019. Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/02/11/russians-lower- their-standards/.

Parker, R., ‘Inside the Collapsing Soviet Economy’, The Atlantic, June 1990 issue. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1990/06/inside-the-collapsing-soviet- economy/303870/

Teon, A., ‘China’s Economy, Unfair Trade, And The Role Of Government’, Greater China Journal, 15 October 2019. Available at: https://china-journal.org/2019/10/15/chinas-economy-unfair-trade-and- the-role-of-government/

The Economist, ‘Our bulldozers, our rules: China’s foreign policy could reshape a good part of the world economy’, 2 July 2016. Available at: https://www.economist.com/china/2016/07/02/our-bulldozers- our-rules

Zitelmann, R., ‘State Capitalism? No, The Private Sector Was and Is The Main Driver Of China’s Economic Growth’, Forbes, 30 September 2019. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/rainerzitelmann/2019/09/30/state-capitalism-no-the-private-sector- was-and-is-the-main-driver-of-chinas-economic-growth/#6c06003027cb

原文链接:https://www.johnlockeinstitute.com/2020-second-prize-history-essay